Today I will cover a controversial topic: the fat acceptance movement. People are divided on whether or not it is something that should be endorsed, or merely a celebration of unhealthy eating habits. There are plenty of video clips online promoting the fat acceptance movement which contain misleading information about what happens to the human body when it stores too much fat. My goal with this article is to fill in the gap about the actual health effects of obesity that normally aren’t trending on TikTok, and discuss how this trend affects those living with obesity. I invite you to join me as I dissect what the people – and the data – have to say. You can view the video that I made on the same topic here. I highly recommend that you watch the video since it includes clips of people on TikTok sharing their unique personal experiences with fat acceptance, and you won't find those clips in this article.

What is fat acceptance?

According to our favorite free encyclopedia, the fat acceptance movement, “also known as fat pride, fat empowerment, and fat activism, is a social movement seeking to eliminate the social stigma of fatness from social attitudes by pointing out to the general public the social obstacles faced by fat people.”

There is a tendency to associate this movement with social media, but it actually started way before “doomscrolling” and “swiping right” were a part of our lexicon. Fat acceptance actually started with the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA). The NAAFA was established in New York in 1969, and their stated mission is to “change perceptions of fat and end size discrimination through advocacy, education, and support.” To this day, they continue to promote “equality at every size” and have fought for laws which protect against weight discrimination as a civil right. Around the same time that NAAFA was finding its bearings, feminists living in California decided to start their own movement called the Fat Underground. Instead of solely asking for policy changes related the liberation of fat people, these women wanted to see a change in the way that society placed value on, revered, and even feared women according to their body sizes. They would do things like show up at diet meetings and present facts about why diets do not work – which is awesome because dieting truly is pointless.

Even if Queen Bey endorses it.

In the modern day, fat acceptance is a hot topic on social media. On TikTok, the hashtag “fatacceptance” has 162.5 million views, followed by #fatacceptancemovement with 718,000 views and #radicalfatacceptance at 44,000 views (Note: these numbers may be higher by the time you read this article).

The problem with fat acceptance

From its inception, fat acceptance has been controversial. Interestingly, both people who are fat and people who aren’t fat are divided on whether or not this movement is a positive one. Supporters say that the movement is necessary for combating anti-fat discrimination that is present across society. Opponents say that fat acceptance is akin to telling people that being fat is healthy. I’m drawing a clear line between two camps of people, but there is a lot of variation within the community about what fat acceptance truly means. Let's take a closer look at some assertions made by supporters of the movement.

If you peruse TikTok, you will find people making claims that weight and health are uncorrelated. The reality is that weight can be and often is an indicator of health. Having categories and cutoffs for weight is helpful for making clinical decisions – something that was put into practice on a national scale during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. When it came to light that obese people have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19, they were prioritized for vaccination (see this article, this article, and this article).

You will also come upon videos of people alleging that the obesity epidemic is overblown. This is false. The obesity epidemic is real, and its consequences can be dire both on an individual and a societal level.

Why excess weight should not be normalized

Carrying extra weight on your body is a well-established risk factor for several health conditions. What’s more is that extra weight is not just correlated with these conditions – it can in many cases directly cause these conditions to develop, and make them worse over time.

Now, how does someone know if they are obese, or just have a little extra fat on their bodies? A person who is classified as overweight has a body mass index (BMI) of 25-29.9. A BMI of 30 or more places an individual in the obese category. This is the subset that is most at risk for the health outcomes that I will be discussing shortly.

Now, I know that many of you may be wondering – Michelle, isn’t BMI an outdated and racist tool for assessing health? Well, yes and no. For now, just know that for the average adult who is not a bodybuilder, a BMI of 30+ is enough to raise concerns.

Okay, now let’s cover some basic stats on obesity:

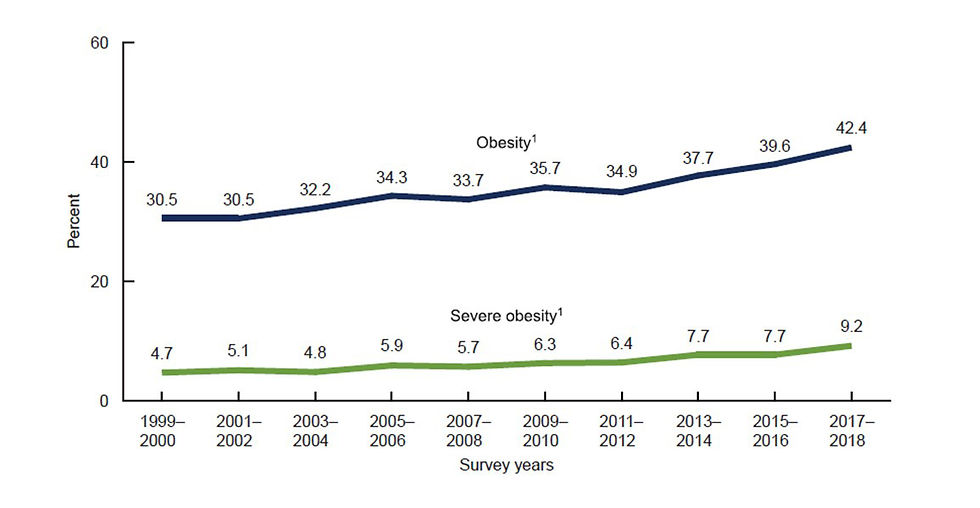

The latest data for the United States comes from the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and it states that an estimated 42% of adults and 19% of children in this country are obese.

Quick side note – we don’t use the straightforward BMI calculation for children. Instead, growth charts are used, and obesity is based on a percentile calculation. If a child is in the 95th percentile of their peers of the same age and sex, then they are classified as obese.

NHANES obesity data for adults.

The prevalence of obesity has been steadily climbing decade after decade. Twenty years ago, 30.5% of the adult population was obese. Now, we are at 42.4%. For children, the statistics are even more worrisome – in the 60s, the rate of obesity was around 5% - now the number of children with this condition has quadrupled.

NHANES obesity data for kids.

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of multiple life-threatening conditions. Let’s take a closer look at some common ones.

First up is osteoarthritis.

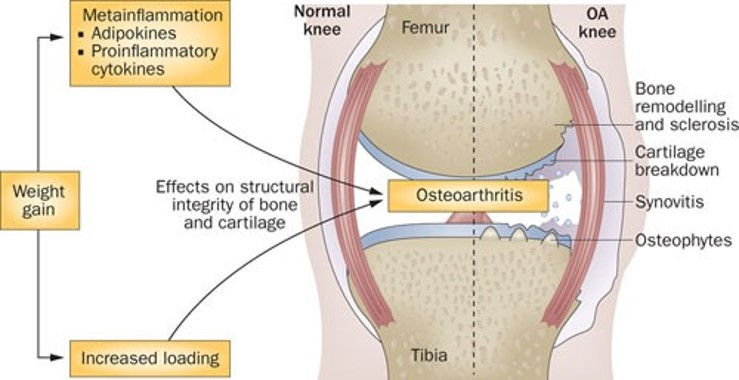

Wluka et al 2012.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the degeneration of cartilage and bone in our joints. In addition to causing stiffness, it can also be quite painful. Studies show that obesity increases the risk of knee OA through several mechanisms, such as increased loading of the joints, inflammation, changes in body composition, and behavioral modification. This last factor is somewhat of a vicious cycle, as obesity can limit mobility and make it hard to exercise, and this lack of movement can in turn weaken the muscles that protect the knee from damage, so the joint gets progressively weaker over time. Losing weight is known to reduce the risk of developing knee OA, and if you already have knee OA, shedding a few pounds can help to improve the function of the knee and slow down disease progression.

Next is obstructive sleep apnea.

Drager et al 2013.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition characterized by recurrent episodes of the upper airway muscles relaxing and blocking the upper airway, causing a momentary pause in breathing which is brief but severe enough to interrupt sleep and cause intermittent hypoxia (aka low oxygen levels). Obesity is a risk factor for OSA, and they actually interplay with one another. Intermittent breathing interruptions caused by OSA have been shown to worsen the metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity.

Now, let's look at gastrointestinal complications.

Camilleri et al 2017.

Obesity causes or greatly increases the risk of numerous gastrointestinal complications, including “gastroesophageal reflux disease, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, erosive gastritis, gastric cancer, diarrhea, colonic diverticular disease, polyps, cancer, liver disease including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, gallstones, acute pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer.”

Next up, type 2 diabetes.

Williams et al 2018.

Obesity is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. This is because when we gain weight, the number and size of our fat cells increase, and this affects the substances that they release. Remember, our fat cells are not just sitting there – they are biochemically active, sending out signals to the rest of the body constantly. Some of these substances are called adipokines, and I want to highlight two of them – leptin and adiponectin. Leptin helps us to burn fat and keep our blood sugar in check, but its effects are reduced in obesity due to a reduction in receptors. The body keeps producing leptin, but it cannot do its job, and so we become less efficient at burning fat and maintaining our blood sugars where they should be. Adiponectin on the other hand is reduced by obesity, and this is turn promotes insulin resistance, a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes.

Fat cells also release lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA). LPA helps to regulate cell growth and survival, the flexibility of our blood vessels, and blood sugar stability. As you guessed, obesity interrupts these processes, too. Cells with too much fat in them respond less effectively to insulin, the key that unlocks the door for glucose to enter our cells and be used for energy. Basically, obesity changes our biochemistry in a way that favors type 2 diabetes.

Finally, let's look at COVID-19.

Sanchis-Gomar et al 2020.

The pandemic seems like it is pretty much over, but considering how life-altering the lock downs, vaccine roll outs, and transitions to unemployment for some and working from home for others were globally, I figure it is still worth mentioning. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified severe obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) as a risk factor for having a worse prognosis, higher rates of respiratory failure, a higher need for mechanical ventilation, and higher mortality after infection with COVID-19. This is because the virus penetrates human cells by binding with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 receptors on the cell surface. ACE-2 expression in adipose (fat) tissue is higher than it is in lung tissue, which means that the virus has an easier time, unfortunately, wreaking havoc in people with a greater volume of fat tissue.

Obesity is also unfavorable from a financial standpoint. Annually, $190 billion dollars are spent in the US on obesity-related healthcare expenses, and that figure accounts for direct costs such as surgery, as well as indirect costs such as lost wages.

I think it is fair to say that obesity is not something that we want to treat as innocuous. So, how should we as a society approach this very real, very human issue? Should we gather in a circle and shame people who are obese until they internalize so much guilt and shame that they eventually lose weight? Of course not, but this does happen - metaphorically speaking.

Are medical providers failing their patients?

While perusing TikTok, I found several videos under #fatacceptance that highlighted the reality of weight stigma. Unfortunately, some medical providers go the route of trying to scare or shame people into losing weight, and this is not helpful for anyone. While it is unfortunate that these people went through these demoralizing experiences, it’s great that they are sharing their stories because change often starts with awareness. Access to proper healthcare is a fundamental right, and if some people are interfacing with providers who are biased and refuse to properly assess them before coming to a conclusion, then the system needs to be shaken up.

When has this ever worked for getting someone to develop better habits without hating themselves?

I have had patients share with me, tearfully, stories of past medical providers laughing in their faces, berating them, or telling them not to come back again until they lose weight. To tell someone that they are undeserving of care until they reach a certain weight is not okay.

In my own practice, some clients opt to not track their weight when they work with me. This has never been a problem, because what I teach about food is independent of weight. From my point of view as a dietitian, the key is to empower people to make the choice themselves to develop healthy habits that will be sustainable for them. If weight loss is a byproduct, cool. If it’s not something that a patient is interested in, also cool.

Some fat acceptance advocates say that weight stigma in the medical field is a symptom of a broader culture of fatphobia. Let’s talk about that.

The culture of fatphobia – real or imagined?

Fatphobia, as the name implies, is a fear of or aversion to fatness. I do agree that this is a pervasive ideology in this country, and it is ironic because rates of obesity are climbing, meaning that more and more of us are joining the group that has for decades been treated as “less than.” The fat acceptance advocates deserve points for drawing attention to fat discrimination in the workplace and beyond. However, there are some cases where the word seems to be misapplied.

The media does tend relegate fat characters to best friend/comedic relief roles, and the intersectionality of color and gender can make this even more true for Black women.

Some claims of fatphobia have left me with feelings of uncertainty, as I don’t think that any of us should always expect life to be accommodating. For example, I am a tall woman with feet that are in proportion to my long body. If I go to a store and they don’t carry my shoe size – which has happened to me countless times – should I feel discriminated against? I personally don’t – I just keep looking elsewhere until I find what I need. I have been tall all my life and I understand that most women in the US are much shorter than me, therefore most stores do not keep a stock of shoes for outliers like myself. This begs the question - when is it fair to label something as fatphobic, and when does it become a matter of needing to adjust expectations? For example, if a hotel does not have extra large towels and extra large seats, is that discrimination against fat people? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

There are also claims on TikTok that the mere act of exercising with the goal of losing weight is a symptom of fatphobia. I disagree with this. People who exercise to lose weight are not simply running away from fatness. They are running towards being able to go on vacation and walk around without getting winded as quickly. They are running towards being able to put on their socks without someone else’s help. They are running towards being able to feel that sense of achievement that comes with working really hard at something and slowly but surely getting those hard-earned results. These are all things that clients have said to me after losing weight.

I also want to address the claims that posting before and after photos showcasing a weight change is a bad thing. Social media is a space for people to brag about their lives and share their happy moments.

A little virtue signaling here, a little humble bragging there... we all know the game we're playing.

If someone works hard to lose weight and they want to post about it, good for them! Only they can truly understand what that transition means for them and why they felt it was worth sharing. Asking people to not post about losing weight because other people look like their pre photo is like asking people not to post when they get a new job because some people are unemployed. Life is a mixed bag for everyone, and we are all entitled to celebrate our achievements.

Reddit commentary on fat acceptance

To get some more opinions on the topic, I decided to peruse Reddit.

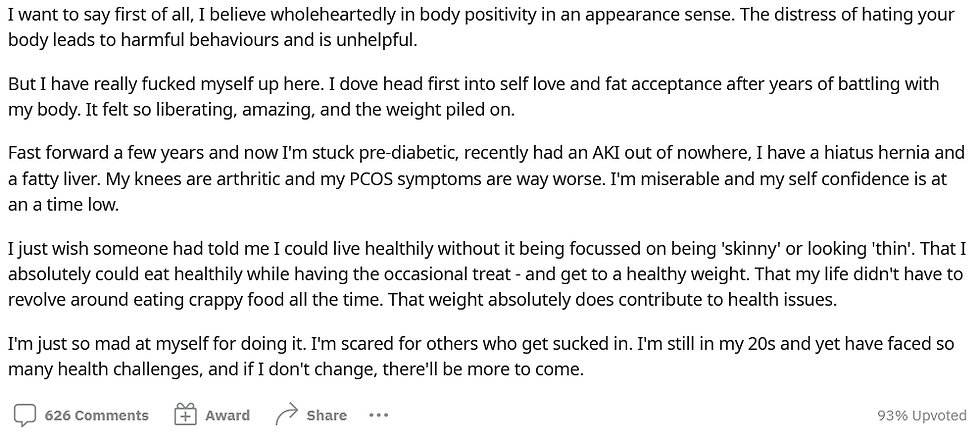

This user posted that they “escaped” fat acceptance, and doing so took their life in a more positive direction:

This user shared similar sentiments:

Another user posted that fat acceptance should not exist.

While yet another user expressed that fat acceptance is unhealthy.

This user provided a perspective that encapsulates all of the positive aspects of the movement and what I believe it was intended to be about decades ago when it began.

Conclusion

The fat acceptance movement is controversial, and people who choose to be a part of it can internalize the message of fat acceptance differently. For some people it helps, for others it hurts. Some people take it to mean fat promotion, others take it to mean simply treating fat people as fellow humans. The truth is that obesity does come with health and financial consequences, and it is okay to be honest about this while still promoting love.

Ultimately, I think that nobody should have to wait to feel worthy of giving and receiving love. Life is just too short and fickle for that. You should work on loving yourself in the now, and if loving yourself means losing weight so that you can do X thing, good for you. If loving yourself means staying exactly as you are, then that’s also okay.

If you learned anything new or think that someone you care about could benefit from this information, share this article, and subscribe to the blog for regular updates on commonly asked nutrition questions.

Enjoy today!

References:

NAAFA website: https://naafa.org/history

Links to articles on the link between obesity and COVID-19 morbidity and mortality:

CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

Link to 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) obesity data: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity

Article on osteoarthritis: Wluka, A., Lombard, C. & Cicuttini, F. Tackling obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 9, 225–235 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.224

Article on obstructive sleep apnea: Drager LF, Togeiro SM, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi-Filho G. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Aug 13;62(7):569-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.045. Epub 2013 Jun 12. PMID: 23770180; PMCID: PMC4461232.

Article on gastrointestinal complications: Camilleri M, Malhi H, Acosta A. Gastrointestinal Complications of Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2017 May;152(7):1656-1670. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.052. Epub 2017 Feb 10. PMID: 28192107; PMCID: PMC5609829.

Article on type 2 diabetes: Williams, J. Asiamah, P. Hamdallah, H. (2018).Type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, what is the link? Open Access Government. (This article has more links to the biochemistry stuff too)

The national cost of obesity: Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012; 31:219-30.

Child growth charts from the CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html

Wikipedia article on fat acceptance movement: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fat_acceptance_movement

Comments